Tryfon Tolides, poet and author of An Almost Pure Empty Walking

exclusive interview with Artemis Leontis

Poetry runs deep in the Greek world, so deep that Greek experiences of the human condition seem intertwined with language and poetry. Who does not feel the resonance of words like anthropos, philos, phos, thymos, logos, nous, or psyche, words shaped and reshaped in the mouths of so many singers of tales: from Homer to Sappho, Euripides to the writers of the New Testament, Yiannis Ritsos to Eleni Vakalo? Who does not appreciate the succinct vision Greek tragedians and lyric poets have given to the perplexity of humanness, what Greeks call the “abyss” of the human soul? Who, when visiting a Greek mountain or island village, or enjoying the intensity of a long, beautiful evening with friends, does not feel the need to put that experience into words that move others deeply?

Tryfon Tolides

Good poetry thrives in Greece even in our unpoetic times. Less recognized is the fact that Greeks living outside Greece and writing in languages other than Greek have been giving voice to their vision. For decades wordsmiths of Greek descent have been honing English with imagination. In the U.S., several have received national awards. Olga Broumas, born in Syros, was the first nonnative speaker of English to be selected for the Yale Younger Poets Series for her electrifying volume, Beginning with O, in 1977. In 1992 Nicholas Samaras, raised on Patmos, landed on the same eminent list of poets with his Hands of the Saddlemaker, a “remarkable” book of “personal intensities, ancient reverberations, and American intonations,” according to the New York Times critic (9/20/92). Eleni Sikelianos, California-raised great-granddaughter of the revered Greek poet Angelos Sikelianos, who is known, like her great-grandfather, for her lush, lyric language, was the 2002 National Poetry Series Selection for her The Monster Lives of Boys and Girls

Now another fresh voice, wise beyond its years, has received national recognition. It belongs to Tryfon Tolides. His poem, “The Mouse and the Human,” was the Foley Poetry Award Winner in 2004. His book manuscript, An Almost Pure Empty Walking, called “a stunning debut,” won the 2005 National Poetry Series, selected by

Mary Karr, and was published by Penguin Books this year. A deeply spiritual writer, Tolides can fi ll the mind and heart of any reader who makes the effort to turn off the distractions and hear the inner voice calling. Tolides has described the process in this unpublished poem.

Calling

Come to the point where, fi nally, you are lost,

wayside-sitting, wind-gazing, train-whistle-listening,

if you want to converse with the invisible presence,

continual, sustained, indwelling, be lost,

be abandoned, so that the heart, the mind, as big

as God, come to the place where you are lost,

so that all your days and the shuttering of each day’s

light and the blue magnetic incomprehensible

jumping and motionless blue of twilight and the fi ne

blackening after, around the incomprehensible

waiting and breathing of trees with their delight-inducing

cloud-depths and freedom-shapes and darting birds,

happen in pure glory, in ineffable joy of consciousness,

so that your senses overfi ll to beautiful muteness,

so that mere being becomes the form of your praise.

Tolides’ poetry entered my life this past summer as I was taking an introspective turn such as he describes in “Calling.” Unexpectedly I received Tolides’ brief note introducing himself and his poetry. “I was born in Greece, in a village of Kozani, and have lived most of my life in Connecticut. The body and spirit of Greece do live

in my poetry....” The back cover of An Almost Pure Empty Walking gave me just a bit more biographical data. The author was born in Korifi , Greece, and moved to America at the age of six. His education led to a B.F.A. in Creative Writing from the University of Maine at Farmington and an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from Syracuse University. I later learned that Tolides also completed a two-year diploma program at the Hartford Conservatory in Jazz Composition. I add this fact because I believe you can hear in his poetry his feeling for texture and phrasing, for the pauses, breaths, and silences in music from guitar to klarina, from Pat Metheny to Petros Lukas Chalkias to the gypsy musicians o Angelos, to Tsimouli, o Minas who’d come to his village for weddings and walk through his horio with the ghambro.

Thirsty for something to read, I reached into An Almost Pure Empty Walking as soon as it arrived and carried it with me for months. I found in it the insight of an old sage and energy and curiosity of a 9-year-old boy. I refer here to four poems from the collection that are also published on two internet sites: www.poems.com/treetol and www.americamagazine.org/poem.cfm?articleTypeID=25&textID=3629&issueID=487. (The rest of the poems in the

collection you will have to read the old-fashioned way, with book in hand.) “Almond Tree” names with audible precision sights, smells, and crackling sounds remembered from a mountain village. “Immigrant” displays verbal habits of an immigrant mother, who does not forget to ask “what I would eat for lunch” even while bitterly complaining, blaming, “hating the mess we’d found” in America. “The Mouse and the Human,” a poem of conscience, which I read aloud to my daughter on her 18th birthday, follows a charge and a duty prescribed by poet Odysseus Elytis when he called poetry a source of innocence, full of revolutionary forces. Finally “I Will Sweep” takes readers into the “dead” of the Greek village winter:

I Will Sweep

What will you do in the village alone in the house with your mother gone in autumn with winter coming? I will sleep with the terrifying and brave blackness at night of the village and of the house. I will sweep the yard

of plum leaves and pear leaves, with the short broom, my back bent. Sweep, clean, tidy up, my arm repeating

a motion until I am woven with my dead into a clear and living braid. Then I will sit in one of the chairs by the white table and wait on the wind, the birds, the ancient scent of the house, joyous and crying.

(An almost Pure Empty Walking 66, reprinted with permission from Penguin Books, a division of The Penguin Group USA, Inc.)

The best way for me to present Tolides’ work is to piece together the give and take of our e-mail correspondence dating from September 15 through November 2, 2006. I kept pressing Tolides with questions, while he used the e-mail forum as a “slight workbook to write out some ideas,” to expand some of the images he has so eloquently condensed in his poetry, and to offer new poems. Here is the product of our exchange.

AL: You were born in Korifi Voiou, Greece. What kind of a place was it when you left and how do you find it now?

TT: A beautiful magical grounding home, haunting, spiritfi lled windfi lled mountainfi lled monopatifi lled stonefi lled

korombilafi lled...place. A village like many, which is dying out. Now, in the winter time, there are perhaps 30-40 people that live there. In the summer the population spikes, but not like it used to. The youngest of the people that live there year round are in their mid-70s. Before I and my mother and brother left in 1972 to join my father in Connecticut (mas efere edho, if you know what I mean, how that works, my guess is that it is common), there were 3 little stores, one periptero, the elementary school was still open, two kafeniea and the population of the village, though it had been dwindling for some time, was at least three hundred people. Two tsangaridhes. Our village priest was still alive (now there is one that comes from Tsotili, one Sunday to our village and the next Sunday to the next village of Chrisavghi). The place was full of spirit and tsakna and manitaria and foties and provata and tsoknidhes and kalives and moures and tiria and psychically rich people and the cemetery was alive at night, the presence of the living people always had the effect of making the dead more living, too, they were always in the air and in the houses with us and the animals. Two churches and fi ve ecclisakia and a bunch of iconostasia. 980 meters up with a spectacular view of many mountains around us there, including Smolikas and Vasilitsa, and Ai’ lias, and Grammos. A bus twice a week for trips to the local market town of Tsotili.

So the village now. Old houses left. Fewer people returning. Some people come and remake their grandparents’ house in the style of the old stone, but it’s that exactly: in the style of. No more chickens. The butcher shop long gone. The school long since closed. No more stores, periptero. A new kafeneio is being built, but who will go, especially in the winter. I remember hearing the daoulia across the mountain valley at nights during weddings or panighiria at other villages. I remember counting their street lights and looking at the villages sprinkled across the mountains at night, the little constellations of light. They’ll have a mbatzio festival; they’re making some campaign or effort to make publicity and the village has its horoesperidha in August, etc. But the rooted life it had for a few hundred years is pretty much gone.

I love the village, it is home for me, grounding in body and spirit, even without the people. It is a meditation, a simplicity and rejuvenation for my soul. I’ve gone the past three years, though I usually don’t go every year. This past year was the fi rst time I went since my mother’s funeral. She is buried in the village (my father’s village, but she loved it and grew up there, spent many years). She died two years ago in September while she was there. I got there in time for the funeral and the casket cover at the gate door and all the men in the yard and all the women inside my house and in the room with my mother and the flowers from the gardens of the village women, and the cane I had gotten my mother before she left that year and her glasses. She had been granted her peace finally, and I don’t mean because of the death, or for being in the village and in her house, but she had her peace, at last. It was beautiful. I feel so very glad I made it there in time to see her off, to be there holding a candle next to her in the church. It was all very beautiful and moving. She always prepared for the winters in the village, buying and stocking wood, even though she came back to Connecticut for the winters. She always prepared for us to be

together, and there, as a family, you know?

AL: How did you come to the U.S.? Did you maintain ties with Greece?

TT: My family story would take more pages than I’ve written so far, and most of it I don’t know, including why we/I came to the United States.... I don’t think it was a conventional economic betterment reason. I think some germ inside my father, of travel or search or freedom or fl ee, drove him, and then brought (efere) us here. I think I feel that inside myself and so I speculate that it might have been why. In fact I feel strongly about that. But I don’t

know. But I never asked those questions while he was alive, perhaps due to a kind of reverence for what his words might conceal. My mother’s story would take a long time. To me, it has deep pain, and incredible love (the love being what saved her from the pain...). Three things to my mother, God rest her soul. Her love for her two boys (my brother is 11 years older than I), her religion, and her nikokirgio; beautiful and deep in these three areas, and so, capable of imparting each deeply. Put her in a bank or airport or with a book, etc. and she would be utterly lost.

After we moved from the horio to Connecticut, especially in those fi rst years, I would go back every summer (just my mother and I) for the entire summer. So that the continuity to/with that place (and people, dhentra, petres, homa, aera, spitia, spourghitia, helidhonia, fi ta, kapnos, htipima tou rologhiou...) stayed continuous, unbroken. The jewel of it built up inside me. Now it is one of the true lights that lights my way.

AL: What is your “mother tongue”? Do you have one? What language do you think in? dream in? talk to children or animals in? What does this have to do with your language of poetry? Do you write poetry in Greek and English? How do you use Greek?

TT: I think of Greek, the horiatika Greek of my village, as my mother tongue, and this is not restricted to human speech and inflection and gesture alone, of that village place, but certainly the wind, the smell and force of it, the mountains, the old houses I grew up in, the uneven fl oors of thatch and mud, the chickens downstairs and their hay nests. The auli and the sterna in the auli. The stone by stone traceable composition of the houses in those

villages, so that one always saw and knew the presence of human hands, this evidence and coexistence with nature. The spirit of that place goes so beautifully and painfully deep. I was born in a house built by my grandfather, delivered by an old woman in the village with her bare hands. I feel blessed that the fi rst contact I made with this outside world was with human skin and not latex. I think my mother tongue is a rich and deep and beautiful conglomerate of these forces and presences. And many more: the smell of the tsangari’s room when I’d go to pick up shoes that had been worked on....

My mother tongue I think of as a song, a song of place and elemental forces and language infl ected by those first people for me and by that fi rst place. I papadhia next door. I feel I am still speaking that fi rst song, out of deepest necessity, but now through my adopted language of English. I feel sometimes that the force of the song is so strong as to bring me to tears. Sometimes I wonder if having left Greece accounts for some or much of this force, that I have kept something more or less sacred and will NOT let it go. Can not.

The profi ciency of my English is much greater, but when I call my aunt once a week in the village, what I hear through her Greek, and of course through her singular voice, I cannot feel that in any English text or speaking person. The root of her to me and to the first place for me is a deepest language. OoouuuuiiiI krio. M’anapsame

ts’sobes. Tora anevkame ‘pan. Such beautiful and simple drama to their lives. I don’t think I am romanticizing.

...I don’t write in Greek, unless I would write a letter to my mother or to my aunt. Haven’t done so in a while. I don’t think I could really write “poetry” in Greek. But am glad for that Greek/village song which writes itself in the language I am most profi cient (and textured) in.

Perpetual Awakening

You approach your native language

as if for the fi rst time, as of an encounter

after exile, where you learned of perimeters,

peripheries, distance, absence, stillness,

and what is intimate in these, which have

become part of how you encounter.

You and your native language are two winds

amid each other, and each is a fl ower

garden for the other, with white and red

roses of pain exquisite fragrance, lavender,

the shine of bay leaf. You listen

to the sound of your native language,

tongue, voice: song of wind, flower, stone

by stone house, song of sun, cemetery,

old small chapel with sinking roof,

song of donkey with sagging carriage, song

of his gray disheveled humble hair, song

of his shy eye, in a fi eld with one tree,

one shade and all light you meet your native

language again, for the fi rst time.

Even without understanding many words

(though you understand: sea, hand, forest,

violets, leaving, fi refl y) or their syntax,

the music is unchanged, intimate,

eternal, as it sings to your soul, as if

you are singing.

AL: Are there Greek poets you read? other Greek authors? poets or authors (old and new, ancient and modern, non-Greek and Greek) you would like to mention?

TT: On who I am among Greeks, a shoot not off the conventional academic tree... I did not grow up around books. When I moved to the United States from a small village in northern Greece at age six, where we hadn’t electricity or running water, the change was stark, from that place to waiting for the school bus, being plopped down into a foreign land and language, getting dropped off at my father’s pizza place every afternoon, where I did a fair amount of my growing up and observing the world and the short exchanges typical of a pizza place pick up joint. One sees the same people each week, for approximately two to fi ve minutes at a time. There are exceptions: Greek people who were either related to us and would come to visit; or other Greek people who sort of traveled the pizza place circuit, to converse in the Greek way about politics, money, gossip, the quandary of the diaspora, and also to establish a place they could rely on for a free meal now and then. The sense of literariness I might have comes from the mountains and air and people of my village, and also from this working class family setting, with its spinning stools, booths, realty calendar of U.S. presidents and poster of the Parthenon on the wall, jukebox, my

father and his thick accent, my mother staring out the window as if the pizza place were a bus she never wanted to get on in the first place, a public private world, compressed, with its peculiarities, long hours, and strains.

I have felt a failure in my responsibility as a Greek, now writer/poet because, largely, I don’t know, have not lots of literature and history of my heritage. Greeks being proud about those things to a sometimes fanatical degree, I find that being an “artist” doesn’t cut it when I meet with Greek people who have learned I am a poet and have published, etc. They begin to ask me about so and so and to share their take on all sorts of literary and historical facts. Reminds me of the Paul Klee exhibit I saw the other day, how someone next to me said: I wish the curator were here to tell me what technique this is and the context etc. It seems most people bypass the primary encounter with art. So I feel I often fail in my assumed or appointed or expected role of compendium person

to make the Greeks proud etc. Which is not to say that I reject literature as a place where primary encounters can happen. Nor is it to cover the fact that I am lacking.

I think I’ve read, and not extensively, but to get a flavor, poets I think I am/was supposed or expected to read. Cavafy, Homer, Elytis, Seferis, Ritsos. I think one of my favorites is Ritsos. And I learn from all of them not the comprehensive history of Greece, but individual consciousness of the world.

Thus far, my wiring has me set internally to my self and it is from there I feel around. And so the concept of hesychia has a spiritual relevance there, though perhaps not strictly a theological relevance, though I read Philokalia and early desert fathers, but I get from them a state of being more so than a doctrinal system. But I take flavors from the Greek writers. From Ritsos I learn something about pacing and surprise and momentum and juxtaposition and mystery. I’ve mostly read and translated some of his shorter poems, poems I thought I could handle. I also like in him an attention to everyday people and ... life and things and how these are portals to the metaphysical, which almost seems to reside in them. And he is able to isolate, highlight, or freeze human gestures and movements and render them magical or sacred, or imbue them with some ancient or eternal quality. I’ve recently tried reading some Seferis and Elytis in Greek, to hear what is supposed to be my mother tongue. I wrote a poem about the experience. I think I get from Elytis a sort of ecstatic force and will toward a fl ourishing, a richness of texture, an elaborate flight. From Seferis something more sober and, though his poems don’t feel as layered as Elytis’, something of more weight in them, weight in almost a physical sense. Yet there is a lighter but still beautiful song. Cavafy is the lone individual very conscious of himself and the world around him. Self-conscious. I like his epigrammatic poems, though they seem to have more psychic tiredness than the epigrammatic poems of Ritsos.

Homer I have read, in English, the Iliad and the Odyssey. And I’ve read some Euripides and Sappho. I like the extension the tragedians provide from Homer’s laudatory of the hero works to explicitly questioning motivation and heroism itself. I look for patterns, I think. Why is Odysseus, among the heroes, allowed to return undead and, in the end, gloriously to Ithaka, when the guy was basically a ball-buster? And with Sappho, obviously the erotic

nature of the work is very compelling, but also the glimpses into etiquette of her times, and the power of language, of one word, to stir. I recently read the Anne Carson translation and think it is fine work.

I guess what I mean to say is that I read some of the Greeks but couldn’t really tell you much about them or place them. I just take what sticks to my bones, mostly an organic process, and keep going. So I, so far, have that liability, of knowing little or nothing about the Greeks.

I also read Iphigenia at Aulis. When Agamemnon protests a change in Menelaos’ demands, he (Ag.) is wanting a change. When Menelaos relents/comes to his senses, Agamemnon turns back. When Iphigenia says she will die for Hellas, Achilleas only then offers to marry her. Iphigenia: good-bye light that I love.

(I think these sorts of things happen all over the place in the old Greek stuff.) The Greeks had these interesting and keen awarenesses into the perplexity of humanness and the haunting things that are repeated. So potent. Here is a straggler thought. What I get from Samarakis, or Ritsos (or any of the Greeks or other “literary” or non-“literary” influences and experiences) is not a historical or contextual knowledge of the works (that has somehow always eluded me, or I have not aspired to it, or am not cut out for it), and hardly in any theoretical or academic way; but get some scrap of their breathing, pacing, pausing, some of their living breath that my subconscious

notices and alerts me to. It is mostly this type of knowledge I glean from other works. And then that breath, that gesture, begins to circulate and live mysteriously in me, with my breath...

Most of the poets I have read (not extensively and not many) are not Greek. Mostly they are poets of the United States from Whitman and Dickinson on. I like poets who are drawn to the sayingness of their poems. This is perhaps a vague notion, for each poet has his or her music, but I have been affected by poets such

as Stevens, Adrienne Rich, Frost, and Merwin, in part, because their sense of the poem as a rhetorical event is so strong, and yet, strangely, somehow, not overdone (I like e.e. cummings but feel with

him that the rhetorical event can easily become too prominent, and more clothing than body to a poem). It is the same with musicians. I listen to music ranging from the local klarina of Dhitiki Makedhonia and Epiros to American jazz. One of my favorite guitar players is Pat Metheny. He creates a journey, shapes his solos with story and longing. The way music moves and is shaped is not unlike the way a poem moves and is shaped. To consider one is to consider the other. I like the porosity between anything and anything else, where there are two seemingly different languages, yet a communion or exchange happens in some mysterious way, and underneath it all, the “language” is one. This may be a spiritual lesson, too, a lesson to the world in its present deplorable state.

AL: Could you tell us something about the “I” in your poetry?

TT: The “I” in my poems is a focal point for biography, memory, experience, song. The “I” can be taken up in imaginative flourish, in wondering, wandering, but I like to think in service of truth. My “I” doesn’t invent characters or situations. Nor is it tell-all. My “I” is not “the speaker”; it is me, the person, the poet, Tryfon, thinking, speaking, singing, to myself, internally, externally, and to whomever the signal might reach. Oftentimes the “I” seems

to come from the subconscious, or the soul, relating to me what must be noticed, and said. The more I think about the “I” in my poems, the more mysterious and complicated its consideration becomes for me. I resist theorizing about it. I don’t want to come to know something which is likely unknowable.

There are always epoch and cultural pressures which say what goes and what doesn’t. Since poetry is largely written out of the academy, the prevailing forces and politics about what’s acceptable and “smart” and even hip come from there. I tend to write what is called lyric, which I think is offi cially defi ned as I/me centered view out at the mystery of world, including out at one’s own life. I’ve always thought of lyric primarily as musical and the I/me

component irrelevant to that, but fi rst, song, including song through image. But in the academy, there is a push to minimize the “I,” which often stands counter to learnedness and allusiveness. The “I” poem is then considered parochial, slightly crude, behind the times, un-evolved etc. selfi sh. To the extent the “I” is legitimate, it is often contingent upon the “I” delving into a politically correct investigation or itself becoming the specimen to be prodded at, studied.

For me, the “I” is a way of going deep, and toward spirit. Another thing is, when the “I” serves to extend the poem’s experience to the reader’s experience, and through that trust, to enlarge the reader’s experience of (and wonder at) himself and others, and living, I think this is good. In true art, this can also happen when the “I” excludes the reader and increases his awareness of exclusion. Then, “true” is another matter.... For all the savvy and fl ash and brilliant intelligence one sees in poems written by brilliant PhDs in creative writing, and by all those who make it their business to keep up and sort of stay on the cutting edge of developments, there is also a lack of depth and spirit. This might be arrogant or presumptuous of me to say, or plain wrong, but I do feel that the intellect can get in the way of poetry, so that the writers/poets have raced off to some other land and are busy

devouring and reproducing that, it seems.

Nevertheless, of the prevailing trends, one toward cutting or getting to a polished thing (versus allowing for the process or journey of the writing to show) and another trend, toward minimizing or ridding the poem of the clunky and elementary school I/me (or of rendering the “I” into specimen or subject), I do apply some of these to my poems, but not out of policy. Some poems, though they have I/me when fi rst written, the I/me seems not so important or perhaps already implied, and in my case, implied or overdone since other poems of mine already have that overt presence. But each poem is a separate case. I send you one from yesterday, its fi rst, and then, this morning’s, versions. For some reason I had the impulse to take out the “I,” though as I think about it now, the fi rst version—layered with consciousness, perception, self-consciousness, with the simultaneous presences of the “I,” the tree and the experience of the encounter itself—might be, in ways, richer than the second version. Maybe it needn’t be one version or the other. These seem to me, now, two separate poems, each with

different qualities and scopes. They are still drafts, I think.

On the Way to the Museum

to see the Klee exhibit

I stopped by a medium-girthed tree

and its musculature, outgrown

scars, the decisions it had made

about where to go, how

and what to be.

It had rained for two days

but today was spring in October.

The walkway cracks

were bordered darker

because of the rain.

In between the tree’s fat

arm-like roots,

before they disappeared

in their reaching down, tufts

of newer grass, taller,

deeply and luminously

greener, lush to the touch and wet

at their bases

in small ponds the crossing

arm-like roots had made.

I stuck my fi nger into one pool’s

mild muddy water

and sewery decay smell

among the spongy tangle.

A Medium-girthed Tree

Its musculature, outgrown

scars, the decisions it had made

about where to go, how

and what to be.

After two day of rain it was spring

in October. The walkway cracks

were bordered darker

because of the rain. In between

the tree’s fat arm-like roots,

before they disappeared

in their reaching down, tufts

of new grass, taller, deeply

and luminously greener, lush to touch

and wet at their bases

in small ponds the crossing arm-like

roots had made,

pools of mild muddy water

and sewery scent.

AL: What are you working toward?

TT: Besides very generally a manuscript, mostly I’m working at learning to listen and go more precisely and more deeply into the poems, and trying to be in places inner and outer which awaken my alertness to receiving the word. Hesychia allows for the space where poems and life can be considered. I’m wondering about “revision.” The first issue of a poem, its first music, versus cutting and paring it down, polishing toward a concision and brightness. I don’t hold to one approach or the other as a total policy, but each poem needs to be listened to so I might help it say itself as it means.

I’m curious about where I am going, who I am becoming, as a poet, too. What in my poetry will be pursued or emerge. If I were to put together a manuscript which is more or less like the first one, I don’t know that I would want that. But I do not purposely push toward some new experiment or direction. I let it emerge and wait and listen and learn that way. My main job is to keep trusting the impulses, to have faith, to keep writing, if it keeps coming to me, and not to be concerned so much about analysis or pushing some experiment, aesthetic, or theme. I write what I write and in ways mysterious to me, an order or shape begins to take hold of a collection, coalesces.

AL: In describing your work, you used the expression, “going more deeply into poetry.” You also used the word “hesychia,” in which I hear echoes of Greek Orthodox mysticism. What does it mean to go more deeply into a poem. What sorts of inner places does one reach? How are these connected

with outer places? Do you have anything to say about poetry and prayer? What do people say about the relationship these days? Is there a movement of some kind that explores these as parallel processes?

TT: The two sections above are huge questions, full of mystery and paradox. What it means to go deeply into poems: it may be becoming super conscious or fully unconscious. Strange thing is that there might be a point at which these two meet and are in fact indistinguishable, the same thing, so that one arrives at presence, stilled presence, where experience can be harmoniously taken in, or where one becomes experience itself, one becomes not an organ of, but perception itself; reality, being, in communion with the cosmos, with God. Isaac the Syrian speaks of “inebriation” with the love of God, a point at which knowledge and the intellect are subsumed in wonder, in ecstasy, where knowledge is made perfect through faith “to see the radiance of him who is incomprehensible to the intellect and to the knowledge of created things.” So that the soul, “because of her trust in God,… becomes as one drunken, in the awestruck wonder of her continual solicitude for God; and by simple, uncompounded vision, and by unseeing intuition concerning the Divine Nature, the intellect becomes accustomed to attending to rumination upon that nature’s hiddeness.” One way to this life is through awe at what God has

created, all around us. And there is a state, not a method, which makes a way toward this life. That is stillness, according to Isaac. I think I am someone who needs more solitude than the average person. Hesychia, stillness, allows for, is the climate in which, something of seeing, of communion with being and with the divine might take place. Something in me wants this sweetness. And recognizes its value to my sanity and spiritual progress or health. I don’t know. I think it may have to do with temperament. I don’t know if one can aspire toward hesychia if something in his soul isn’t aimed for it already. Or maybe our wills or environments can shift us toward the need for it.

Going into a poem more deeply might be thought of as literal, that is, getting into the meat and blood and bones and pulse and breath etc. of the poem. Or having it, at the same time circulate in you. I memorize other people’s poems and derive this intimacy and benefit of having their music drift and live inside me, having worlds to call upon. And maybe going into a poem means being present, reaching a deep or heightened state of awareness or livingness about the mystery(ies) of life and of creation

Perhaps poetry and prayer require similar discipline. One needs to be attentive, one needs to submit, to be waiting, to be open, to have faith in what one cannot see, in what one does not know if ever he will have contact with (again). To have desire toward mystery, joy, communion, eros (maybe not so with prayer). But a deep, deep

desire for a meeting with what one cannot know, with mystery, with song, with light, with love, with God. Desire to be joined with/to the ineffable.

Hierarchically, I guess we are supposed to go along with the rules, those being that poetry is probably less than prayer. Poetry is a gift by which we can come to appreciate some of the wonder and beauty that the creator allows us, so perhaps to meld the two might be heretical or something like that, especially when one is not

writing good Christian poems, respectful, and one is doing art stuff, unguided, or self-guided. Then, presumably, the devil can easily creep in. I don’t know. Poetry for me feels like such a pure space. Granted, I am not explicitly remembering Christ when I am writing, but there is a source of reverence and truth vital to my engagement

with poetry. It isn’t difficult for me to think that the work of poetry is very close to God, to perfecting the heart, training it in beauty and consciousness, in quietness and watchfulness. But I guess not as strict about avoiding sin and wrong pleasure. I don’t know.

The sorts of inner places one reaches in poetry include delight, ecstasy, stillness, joy, awe, beauty, gratitude, tears, lightness (in both senses of the word), peace. These places are easy to like. One reaches darkness, too, which is also a divine light. One comes to nothingness, or to a sort of Buddhist poise. These locations are not

willed toward. They arrive, by grace, I think. I cannot force my way to any of these places. I don’t know how it happens, but I like to think I taste of them as part of my experience with writing poetry, or being poetry.

But, at times, one must pass intersections of pain or suffering. There is the terror of which Rilke speaks, a necessary place to go to, which does require will or mindfulness to approach (perhaps it is grace here, too, which allows for will or mindfulness). A sort of courage is required, faith, and persistence. But not recklessness, or

something like recklessness. There are scary sorts of places that require a wrong violation for me to get to. My intuition usually keeps me from stirring those up.

Or often I am brought back to zero, whatever my intuitions or efforts, despite them, by some strange force.

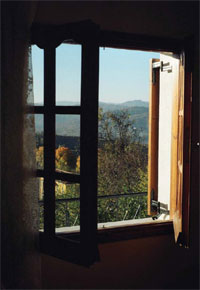

Returning

This morning, something not me returned me to rest, or rest to me. I opened the window to gray October sky. No clarity or air to spike my eyes. As though I were still asleep, a presence silently spoke. I found the static I had made for days around it, from thought, from lust, worn away. Back to quietness. Just as I had begun to think that starting again was the opposite of progress in the spiritual life, a day like this comes. The petals of my progress shed. I come down to a very simple perfection, before bones, before blood, before passion, before mind, this light, eternal nothingness, patience, steadiest, most peaceful thing.

Poems and photographs © 2006 Tryfon Tolides

Interview © 2006 Artemis Leontis,

(with permission from Artemis Leontis and the Modern Greek Program

at the University of Michigan, copyright 2006).